Chapter 1 In Mutema Tribal Trust area are

the Mutema Ruins, which appear to have been places of refuge for lowveld people

from raiding Shangaan. There are several rough stone walls and a square coursed

and bonded single-roomed chamber, for which carbon dates are A.D.I 150 and

A.D.1230. A 17th century European firearm was found on the surface of this

chamber. The site plays an important role in local traditions and tourist access

is discouraged. On Mutzarara, in caves which are basically underground

watercourses widened in places, beads have been found: white bone or teeth ivory

and translucent blue quartz up to �� in diameter and some very small copper

ones, all usually associated with the slave trade and introduced from East

Africa. An object like a wooden container for African medicine indicated that

the cave might have been used by a witchdoctor at some time. Artifacts,

signs of early iron works, burial sites, innumerable primitive articles, and

sets of rock paintings have been found. There is little

evidence of any early settlement by the Bantu. The VaHode tribe reached the

Rusitu valley early in the 17th century, and was probably the first of the

tribes and sub-tribes which moved into today�s Melsetter administrative area

which stretches up to the Odzi and Sabi rivers. The others were the VaGarwe

round Mutambara, the VaNyamazha of Muwushu Tribal Trust Land, the VaRombe on

Sawerombi, the VaUngweme on Rocklands and through the Chimanimani Pass into

Portuguese territory, and VaNyaushe of Ndima T.T.L. who were almost certainly

the last to arrive and appear to have come after the first Europeans were

settled here and whose main body is in Portuguese territory. All seem to have

stemmed from the Rozwe tribe around Charter, Buhera and Fort Victoria, and they

evolved their own language chiNdau. It is estimated that when the

European settlers arrived the total local population was about 5000: it was

certainly static and the numbers were possibly declining. Large tracts of the

district, particularly the highveld, had no inhabitants. Each tribe had its own

sphere of influence, which was constantly disputed both by the neighbouring

tribes and by the Shangaans who raided the area frequently. The main method of

livelihood was the gathering of fruit and the hunting of game, a little

primitive agriculture was practised, and the population shifted from place to

place in the low-lying regions. There was no real settlement and no indications

of permanency. In times of great drought the kraal heads took

offerings of spices, grain, black cloth and snuff to the chief, who entrusted

them to his envoys who carried the offerings to Musikavanhu, a famous rainmaker

in Chipinga District, and it is alleged that the rain invariably came as the

envoys were on their way back home. According to tribal legend the

VaHode (pronounced h�die) or Ngorima tribe was formed by Sahode, a dissident

Rozwe chief who came to settle around the Nyahode river area with a band of

followers. Present-day elders retain in memory the name of every chief since

Sahode. The few people already living here were soon absorbed by the

newcomers through intermarriage, and the new tribe retained many of the parent

Rozwe customs, one of the most significant being that chieftainship passed only

from father to eldest surviving son and about a year was allowed to elapse

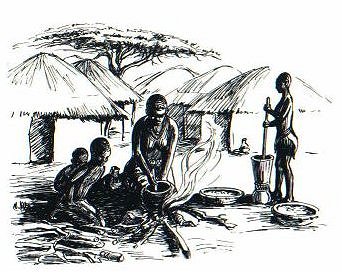

before a new chief was installed. The tribal lands covered a variety of altitudes, soils and

rainfall, so the cropping of cereals, beans, sweet potatoes, pumpkin and ~,inach

was a reasonably simple matter. Wild fruits, herbs and mushrooms were abundant

and honey, flying ants and caterpillars were often available. Hunting the

abundant game or trapping fish or fowl supplemented a diet otherwise provided by

their own domestic cattle, goats and chickens. Ironstone and a wide selection of

indigenous woods were available for fashioning their implements and there was

clay for making pots. The tribe enjoyed peace and comparative prosperity until the

mid-l9th century when the first of the Shangaan raiding parties appeared on the

scene. The chief at that time, Kufakweni, had as a young man sought adventure

with the ranks of the Zulu Zwangendaba who was raiding his way through Rhodesia.

Kufakweni�s name was changed to �Ngorima� following an angry remark he once made

in reply to an accusation that, while he wasted time in adventuring, others were

engaged in the more important task of hoeing the gardens. �Well, I am hoeing

with the spear�, he said. (To hoe in chiNdau is �ku-nina�.) Ngorima organised the tribe on a defensive basis with

lookout posts strung along the perimeter of his country, and successfully held

the raiders at bay for eight years, and on more than one occasion he fell upon a

raiding party before it even set foot within his territory. He was an audacious

leader and the tribesmen were proud to call themselves the Ngorima people. Ngorima�s son became chief and settled on the banks of the

Rusitu river, quite happy to accept Gungunyana, who had succeeded Mzila in 1884,

as paramount. The remnants of the old Hode tribe, many now with Shangaan blood

in their veins, gathered round the new Ngorima and a tribal unit was again

established. It was at this stage that the first Europeans arrived in the area,

and the position of the chiefs Kraal influenced the siting of Ngorima Reserve.

The second Ngorima moved from the new Reserve in 1912 to live near the ancestral

home on Tilbury, where his son and grandson lived in turn, and this policy of

living apart from the mass of their people weakened tribal cohesion for some

years until the chiefs came back to live among their people in Ngorima Tribal

Trust Land. Traditional burial grounds of other local chiefs are to be

seen at Mbundirenyi on Dunblane and Tsanza on Lindley North facing the

mountains. The VaUngweme have used these groves of trees walled with

stone. According to the list of chiefs, the VaNyamazha came to Muwushu,

Biriwiri and Nyanyadzi about 1800. Some of the people were led by a spirit to

what was later known as the farm Cyclops where they found a man, masonga, who

belonged to no particular tribe, living alone off fruits, and settled near him

and were called the Nyamazha, the Unknown; the story goes that these tribesmen

took refuge at the top of Nyamazha hill and were all slain when Gungunyana�s

people raided, and the gwasha then became a sacred place which may be visited by

tribesmen only with spirit approval and where special offerings are made to

propitiate the spirits. The VaNyamazha chiefs were buried on a small hill called

Teterera, and it was customary for anybody wishing to cross Teterera to talk all

the time or make some continual noise, or else he would see strange things and

eventually die. In 1899 Gungunyana established his headquarters at

Manhlagazi, about 50 miles north of the Limpopo river and some 120 miles from

its mouth at Delagoa Bay, and it was to Manhlagazi that later visits were made

which were associated with the settlement of the Melsetter area.

|

There is

evidence of the early inhabitants in various places. On Heathfield Estate a

proclaimed National Monument consists of a large series of abstract engravings

�circles, dots, lines and meanders � pecked on flat, horizontal rock surfaces,

probably the work of an Iron Age people.

There is

evidence of the early inhabitants in various places. On Heathfield Estate a

proclaimed National Monument consists of a large series of abstract engravings

�circles, dots, lines and meanders � pecked on flat, horizontal rock surfaces,

probably the work of an Iron Age people. The rock paintings in the

Chimanimani Mountains, commonly attributed to the Bushmen, tell a story: they

lived here, they saw elephant, buffalo, eland, reedbuck and other lesser

animals; they hunted and killed these animals; they danced. Suddenly they

departed; there is nothing in their rock art to show the arrival of the Bantu as

is depicted in other parts of Rhodesia, and no clue as to why they went.

Certainly, following the departure of the Bushmen, perhaps causing it, came the

first waves of the Bantu pressing down from the North.

The rock paintings in the

Chimanimani Mountains, commonly attributed to the Bushmen, tell a story: they

lived here, they saw elephant, buffalo, eland, reedbuck and other lesser

animals; they hunted and killed these animals; they danced. Suddenly they

departed; there is nothing in their rock art to show the arrival of the Bantu as

is depicted in other parts of Rhodesia, and no clue as to why they went.

Certainly, following the departure of the Bushmen, perhaps causing it, came the

first waves of the Bantu pressing down from the North. All the tribes held special ceremonies

to ensure good rains. In Ngorima T.T.L. the chiefs ceremony was the Masoso in

October, when free beer was provided and an ox was slaughtered, there was

dancing and everybody was allowed to talk freely for a day and a night. Anyone

could hold other rain ceremonies after the chief had held his, and all had

special rituals laid down for procedure, including items such as the behaviour

of the sacrificial goat and whose duty it was to brew the beer and to carry the

beer and the meat.

All the tribes held special ceremonies

to ensure good rains. In Ngorima T.T.L. the chiefs ceremony was the Masoso in

October, when free beer was provided and an ox was slaughtered, there was

dancing and everybody was allowed to talk freely for a day and a night. Anyone

could hold other rain ceremonies after the chief had held his, and all had

special rituals laid down for procedure, including items such as the behaviour

of the sacrificial goat and whose duty it was to brew the beer and to carry the

beer and the meat. About 1873 Mzila, then chief of the Gaza people, sent three

powerful groups which made a combined and successful onslaught. Ngorima escaped

with his nearest relatives and a loyal bodyguard after carrying out a scorched

earth policy, and decided to get Lobengula�s support to reinstate him, in return

for which he would offer his allegiance. On his journey across country to

Matabeleland he was dissuaded from this plan by Chief Gutu who offered him a

place to live in today�s Victoria province. He eventually died and was buried

there, and later his bones were disinterred and brought back for reburial near

the old Kraal site on Tilbury Estate.

About 1873 Mzila, then chief of the Gaza people, sent three

powerful groups which made a combined and successful onslaught. Ngorima escaped

with his nearest relatives and a loyal bodyguard after carrying out a scorched

earth policy, and decided to get Lobengula�s support to reinstate him, in return

for which he would offer his allegiance. On his journey across country to

Matabeleland he was dissuaded from this plan by Chief Gutu who offered him a

place to live in today�s Victoria province. He eventually died and was buried

there, and later his bones were disinterred and brought back for reburial near

the old Kraal site on Tilbury Estate.