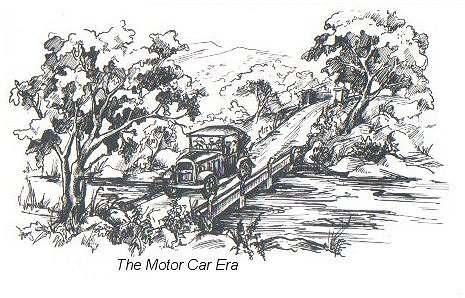

Melsetter, with its main road still very bad and the internal ones

mostly non-existent, was now right into the

motorcar

era. Many difficulties

described went on beyond the 1930s, and travelling continued to be a hazardous

experience. The road over the mountains was narrow, steep, winding and muddy or

dusty according to weather. Everyone tried to avoid travelling towards Cashel on

R.M.S. days, because it was a most unpleasant experience to meet a Railway lorry

round a corner when one�s own car was on the outside of the road and there was

only just room to pass one another and a terrifying drop on one�s own side of

the road.

For the 98-mile journey to Umtali four hours were allowed for an

uninterrupted run, but punctures and other mishaps often lengthened the time,

and a day return trip was seldom attempted. The condition of the road was a

constant cause of concern and complaints were also made about the gates which

were a distinct setback to tourists and so tedious to regular users.

During the early 1930s a great improvement was the laying of strips for

the first 25 miles from Umtali to the Mpudzi river, when the very bad sandy

stretches which had caused so much trouble were at last eliminated. Strip roads

were an advance, but there were snags: the verges were apt to become very

washed-out, the clouds of dust which rose up as cars and lorries came off the

strips to pass one another could be very dangerous, and the roads were laid on

tracks which had grown up with oxwagon traffic and wound in and out of trees and

round any obstructions so that there were many dangerous blind bends.

On trips away one never knew whether one would get back on the day

planned, and everyone always took blankets, a kettle and iron rations in case

one was stuck for the night, and chains and spades were normal equipment. Floods

and swollen rivers held travellers up, and roads were turned into impassable

bogs or rendered so slippery that cars skidded broadside down the hills. On

occasion travellers had to abandon their cars and walk home, slipping and

sliding in the dark on the muddy roads.

In 1930 the Road Motor Service was accelerated: the lorries left Umtali

at 7.15 am. and arrived at Melsetter at 5.15 p.m. The European passenger fare

for the circular route. Umtali-Melsetter-Chipinga was advertised at �4.

Passenger accommodation was two seats in the cab beside the driver, on which

three people could just be squeezed in. A few months later the circular trip was

improved by the introduction of two lorries fitted with semi-passenger bodies to

accommodate 6-8 passengers and to carry about two tons of mail and parcels.

Tickets for the three-day round trip, including hotel accommodation at Chipinga

and Melsetter, then cost about �5.

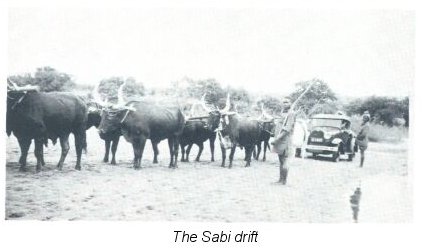

Travelling to or from the west the Sabi river had to be crossed by the

Sabi Drift which was open for motor traffic during the dry season, usually from

May but some years the river was at the deep water stage until July. A span of

oxen was kept on the Fort Victoria side to tow motorists across for �1, and was

summoned by ringing a gong and beating a drum kept on the river banks or banging

on a big sheet of iron hanging from a tree. Crossing the mile-wide drift was

supposed to take about half an hour, but travellers had to allow another hour

for the oxen to be collected and in-spanned and, if necessary, brought

across to the east bank. The in-spanned oxen drew the car over

the sandbanks and through the water, which in places came

through the floor into the car and it was in- advisable to carry

luggage on the runningboards. The ox driver watched the car�s front

wheels carefully and directed the car driver to keep in line with the

direction of travel.

Rose retired and Dr. Kennedy was posted here as District Surgeon for a

short period, and then Melsetter was without a doctor for some months until Dr.

D. M. MacRae took over in 1931.

Many efforts were made to get a golf course going, and during the

decade courses were laid out in front of the hotel and near the racecourse on

which games were played, but interest flagged, revived and flagged again.

Occasional games of rugby and hockey were played on the Sports Ground. The

Gymkhana Club was very active, with the annual Meeting a very big event well

supported by local and outside horses and riders.

The Tennis Club prospered although the courts in the dip between The

Gwasha and the School road had two big disadvantages: the sun was off them by

about 3 p.m., and the stream which flowed between them washed away part of both

courts for many years. The Club paid the V.M.B. 1/- a year rent and 10/- a month

for upkeep until 1936, when the Club was charged 10/ - a year for the lease and

kept up the courts themselves. Matches against Chipinga and Cashel were played

frequently, and many happy tennis afternoons ended with a singsong around the

hotel piano, and the service hatch between bar and lounge has memories for many

Melsetter residents who passed through it.

By 1930 there had been a distinct rise in the value of land:

applications for loans showed that land was being acquired at prices up to 500%

above its previous value, which was attributed to the improvement of roads, but

in Parliament John Martin protested strongly at the continued neglect of

Melsetter by the Agricultural Department.

Miss Elmina Doner came straight from Canada to Rusitu Mission in June

1930. From Umtali she travelled on the Railway lorry with the Rev. Clyde and

Mrs. Dotson to Melsetter, where Hatch met them with a new 5-ton lorry which was

still an event in the district. The three boys in the back had every little

while to get out and work on parts of the road, filling washouts and removing

boulders, and it took most of the day to reach Rusitu.

Dotson was the Station head and a man of all jobs. In the school Elmina

joined Alma Gahm who had come in 1926 and Lillian Taylor who had started there

in 1929. Elmina taught in a little mud hut which had small holes for windows; a

board painted black stood near the door; and at a table down the middle sat the

nine pupils. They were teen-agers from 12 up, one of whom is now a doctor and

another a teacher; they used scratchy pencils on slates, and had one small

English book for each to learn the English language.

Nursing under those conditions was not easy, and the fact that Elmina

had taken a nursing as well as a teaching course was very useful because there

were lots of emergencies. One crisis was when Ruth Dotson, aged about two, had

fever. Katie Allen, the nurse, did everything possible for her, but at last had

to tell the parents that they must try to get her to Mount Silinda Hospital. Mr.

and Mrs. Dotson started out that night with Ruth and Miss Allen. The Nyahode

river on Bloemhof was very full but they drove in and just about in the middle

they stuck on a boulder, the engine died, and there they sat with the flood

waters rushing past, sometimes almost lifting the lorry. There was nothing to do

but pray, and next morning Fred Delaney pulled the lorry out with oxen. When it

was dried off they were at last able to get on to Mount Silinda, where Ruth

recovered.

It was difficult to get patients to come for treatment, especially the

women, as their husbands would not allow them to come to the maternity hospital

to have their babies, and when they were nearly at death�s door they sent for

assistance and it was then so often too late to be able to help them.

During the rains the Mission was sometimes completely cut off when the

Nyahode river was in flood. Once when they could not cross all the Mackenzies

who farmed on Killin and all the Rusitu folks stayed at Olive Cliff, where Mrs.

Delaney kindly spread two rooms full of blankets and they slept on the floor.

Other friends who were most welcoming and kind were the Cronwrights in

Melsetter.

On a visit to Mozambique a group, with Mission pupils as carriers,

walked 150 miles on a preaching and inspection tour, trying to find the people

and acquaint them with the mission and its aims. They had stopped in the forest

and got everything out ready to eat when suddenly they heard the growl of a

leopard close by. In complete silence everything went back into the baskets, the

baskets onto the carriers� heads, and all moved off very quickly.

Another time Elmina was the only European on an expedition when they

heard elephants tearing down trees and pulling off branches, but could not see

them clearly because of the forest. The leader signalled for her and the girls

to get well to one side, while he and the boys lined up on the side nearer the

elephants and they carried on. Later she asked one of the boys, who was armed

with a little stick about two feet long, what he would have done if the

elephants had charged. �Oh�, he said, �I don�t know. But anyway they would have

killed us boys first.�

There were many firsts in those ten years: The first woman to come to

hospital to have her baby there, who spread the word around: �Oh, it is just

wonderful how you are taken care of; you just lie there, and everything is done

for you.� The first twins who, as the result of Mission teaching, were allowed

to live: people watched them for years, expecting some calamity to come to their

family, but they grew up and astonished everybody. The first young man to

build a house for his bride instead of taking her to his father�s home: the old

people shook their heads and wondered who would teach her anything. The first

permanent roof on an African house, of which the owner was very proud, and went

around saying that there would be no more cutting and hauling thatch, and no

more leaks in the house. The first woman to have a sewing machine, around whom

crowds gathered to get her to sew for them. The first ploughing with oxen, when

an old mbuya sat on a rock at the side exclaiming: �Look, look, how fast it

goes.�

Superstition and ignorance hampered the people, who would eat wild

fruits but would not plant fruit trees or make too good a garden in case

somebody should bewitch them; nobody thought of making a permanent house and

they moved from place to place often for superstitious reasons such as having to

move away from spirits if someone got ill. Dotson translated the Bible

into chiNdau, assisted by the Rev. Makinase Bgwerudza, the Rev. Mr. Marsh of

Mount Silinda, and others.

Melsetter Township was originally laid out with small stands on a grid

system, most unsuitable for hilly terrain, and no Commcmage plots were laid out.

In 1931 the V.M.B. was advised that a new survey was due to be carried out very

shortly; and there followed eighteen years of frustration waiting for that

survey, while the V.M.B.�s regular and frequent letters were seldom acknowledged

and Melsetter suffered from unfulfilled promises and the complete ignoring of

its very existence at times, let alone its needs. In 1932 the Secretary for

Agriculture in person told the V.M.B. that a representative of the Department

would come to select suitable sites for commonage plots, and in 1933 the

Minister of Agriculture came to discuss the matter, but nothing further

happened.

In the meantime the V.M.B. had immediate problems needing attention.

The water supply caused concern, with blockages being attributed to various

causes: residents diverting the furrow at unauthorised times, moles, dead frogs,

porridge being washed in it, the furrow being diverted to a resident�s fowl-run,

and horses drinking and crossing:

the N.C. threatened to forbid horses being

kept in the village if there were continual complaints about the water but it

was pointed out that this would be a great hardship to people who rode in ahd

wished to offsaddle there. The Watercart to the Police Camp did not comply with

the Width of Tyre Ordinance and so damaged the roads. The water supply was

doubled through work at the source, and an experiment was carried out of

paving a section of the furrow with stone, with piping under the bridge.

The stream between the Police Camp and the village was dammed and an

openair swimming-bath was opened. The Dutch Reformed Church objected to there

being no shelter round it as they considered it a threat to moral life. The

V.M.B. disagreed with this view, but a few months later the project had to be

abandoned in any case as the dam would not hold water.

The upkeep of the roads was a matter of longstanding concern, with

wheel-harrows the main equipment although on occasion a scotchcart and four

mules was hired at 1 / - a load for carting gravel for the streets.

The early-planted gum and cypress trees needed constant attention.

Silver wattles kept on getting out of hand and having to be eradicated: each

time this was done success was reported but each time the success was

short-lived, and fireguards were also a recurrent problem.

In the 1930s Dr. MacRae was foremost in advocating the planting of

ornamental trees, and was supported by the V.M.B. in arranging for pruning and

tidying and labour. Over 1 200 trees were planted on the commonage in 1932, and

a further 1 000 cypresses in The Gwasha grounds.

In 1931 the Chipinga Magistracy was established and was then

independent of Melsetter. The V.M.B. agreed to act as the Memorial Hall

Committee, and their first move was to re-open the library with an annual

subscription of 10/ 6d per family. They spent �10 on books, more money of

shelving, and a Library sub-committee was formed.

A plaque was attached to

the front wall of the Hall:

1914� 1919

IN HONOURED MEMORY OF

J. D. BINDE A. L. BRADBURY J. P. GIFFORD H. C. LOWRY

A. MAYNE T. J. PINE-COFFIN H. J. SIMPSON

MEN OF MELSETTER DISTRICT

WHO NOBLY RESPONDED TO THE CALL TO ARMS

AND WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR.

GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS.