Among the problems which have resulted from the Irrigation Schemes is the

breakdown of tribal disciplines through the traditional leaders, the chiefs and

the headmen: people have had to be brought in to the Schemes from many parts of

the country and this has resulted in a conglomeration of people with no united

purpose, single culture, discipline or social custom, and there is not the same

respect for tradition and authority on irrigation schemes that one finds in the

dry land areas.

There is also a big population pressure and it is impressive

that the 26 000 acres of Ngorima and Ndima support a population of approximately

10 000, who are moving very fast into a cash economy. Government assists with

the establishment of councils and co-operatives, and through Agricultural

Extension the crops best suited to the area and which will bring in the best

returns are being established. Farmers have done very well with a variety of

crops including coffee, pineapples, bananas, grains, vegetables and spices: one

farmer has succeeded in educating his children and has sent one to university in

England out of his profits.

Ngorima is the only T.T.L. in the Melsetter area to have a Council, and

it is having a struggle to function well: the Councillors have been taken on

leadership courses and to see functioning Councils in other areas, and while

they themselves are enthusiastic and keen on improvement, they find that the

people are not yet ready to accept radical changes and have to be educated

slowly. Chief Ngorima, the fifth in line, who was recently elected a Senator in

the Rhodesian Senate, is progressive, but finds that he cannot move faster than

his councillors will allow: if he goes too far ahead of them he may lose their

confidence.

The other chiefs will not have Councils in their areas: their attitude,

and that of their people, is that the modern Government is European, and they

prefer that Europeans should continue to govern them. There is resistance to

their being ruled by their fellow tribesmen as they do not trust one another �

with some reason, as there have been many instances of people in executive

offices using public money for private purposes.

The Chiefs had great influence, but since their powers were restricted

after the advent of the Europeans they have become withdrawn and inclined to

consider that their main function is that of guardian arid custodian of

traditional customs. This has made them ultra-conservative and not interested in

promoting change. Government authorities are battling to prove to them the need

for beneficial proaress. Many of their people have travelled and lived in towns

and entered into activities which are different from the tribal ones, and these

people are apt to look down on their chiefs as insufficiently progressive.

In all the T.T.Ls. great developments have taken place with Government

assistance particularly since the last war. Before that there was resistance to

such things as modern medicine: the tribesman preferred to go to his nganga

whose ways and methods he understood, and even today he is happy to consult with

tribal spirits, the mondoro or Vadzimu, at every opportunity, particularly to

seek supernatural methods of treatment when modern methods have failed.

The early resistance was gradually overcome when modern methods showed a

quicker, easier and less painful cure: the prevention and cure of malaria and

the quick results of aspirin were much appreciated and injections have made a

great impression. It has come to be recognised that European medicine is

superior in many ways to treatment by the nganga and herbalists through the

tribal spirits, but there are well-known witchdoctors around here who are still

consulted on occasion.

Before the war there was resistance to education and many local schools

were only a third full. When encouraged to send their children to school, the

kraal heads and the parents said that they and their parents had managed

without education and they did not see why their children needed any. Sending

them to school would mean a great upset as each child had certain duties to

perform: the girls had to fetch water and wood and the boys had to herd the

goats and cattle, and if they went to school there would be nobody to do this

work. Sometimes when Government officials went round they found only the parents

at home � the children had been sent up into the hills to hide.

The need for education was felt first in the urban areas which cannot,

however, be isolated from the rural areas as there is constant communication

between them. When buses became regular there was much travelling between town

and country, and people who had seen something of life outside the tribal areas

realised the need for more education and literacy and brought home their ideas

and were assisted by returning soldiers who had seen service in other countries.

Other contributory factors were newspapers in the vernacular and the influence

of the radio.

After the war educational facilities developed rapidly in Melsetter.

Mainly under the Missions many primary schools were established and Secondary

Schools opened at Mutambara, Rusitu, Biriwiri and Nyanyadzi. 90% of the

children of the district can now get five years of schooling at least: there is

a fallout from Grade V and only those with marked ability can go forward to the

secondary schools, but the number going to Upper Primary Schools is probably

higher than in other districts, in spite of the fact that in a few very remote

areas little need is yet felt for any education.

With their religion of ancestor worship, individuals even today get

into situations where they feel that there is nothing that they themselves can

do, and go to their spirits to seek advice, although in some instances much of

the ritualistic preparation to ensure the proper approach to the spirits has

fallen into disuse because so many who were qualified to carry it out died

without passing on their knowledge. Recently chiefs have been criticised for not

carrying out the proper processes for propitiating the spirits, and some of

their ancient customs are being revived. When Chief Tamanewenyu of Muwushu died

in January 1970 every cockerel in the Reserve was slaughtered on the orders of

his son, one of the VaKuru.

Various animals, birds and insects are associated with the spirits and

are taboo and may not be killed or eaten.

In tribal custom the extended

family is still very strong with specific rules for individuals to inherit their

responsibility of looking after and caring for relations who may be left without

visible means of support. In 1968 there was some food shortage, and European

organisations handed out food to those who they considered were in most need of

it, without consulting the chiefs. This led to a certain amount of criticism, as

it was felt that the Europeans were breaking the custom of extended family

relationships, and if somebody breaks the cycle then the relatives consider that

they are no longer responsible for the person who has been supported by

outsiders.

There are seven Purchase Area farms in the District and these, under

title, are being developed satisfactorily. Most of the Tribal Trust Lands have

flourishing business centres, and in all road improvement has led to general

development.

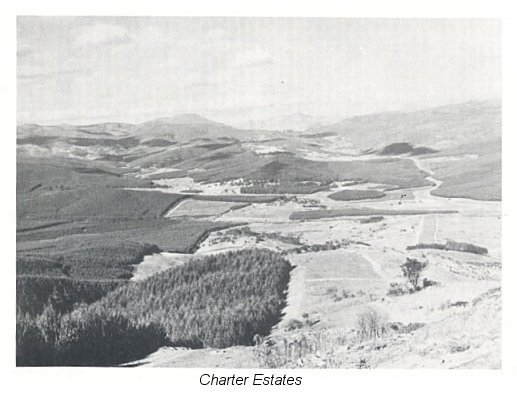

The forestry Companies carried on tree planting and expansion. All have

fire towers, and between them they have well over 1 000 miles of internal roads

built and being maintained. The Forestry Commission, Charter and Tilbury have

their own sawmills, and on Gwendingwe the sawmill is run by a sister Company, A.

C. Moore (Pvt.) Ltd., to whom the Estate delivers the logs and the further

handling is an independent process. Heavy timber lorries transport timber from

Melsetter to Umtali in a steady stream.

Melsetter�s appearance has changed with the coming of the Companies as

tree-clad hill-sides cover vast areas, but the magnificent views may still be

seen. Afforestation is established, and it is envisaged that industries based on

wood may follow. One snag appears in the sawmills� incinerators, which belch

forth smoke all day and night and spoil the lovely clear air.

The Rhodesian Wattle Co. is small by world standards, and when the

world extract market became oversupplied they considered ways of diversifying

and invested in cattle which are run on all the Estates: on Charleswood wattle

was given up entirely in favour of cattle and large acreages of maize grown as

feed. Sugarcane is grown on some Chipinga estates, and raw sugar is manufactured

at Silverstream factory during four months of the year, with the production of

wattle extract limited to the other eight months. In 1969 the Rhodesian Wattle

Company was bought by Lonrho Ltd.

The Forestry Commission has a Research Station at Muguzo, where forest

trees from all parts of the world are raised for experimental planting in

different parts of the district. Sample plots have been marked and measured on

Commission land and on most private forests.

On Charter Estates planting rates were increased from 1 500 to 5 500

acres a year spread over eight sections, each of which is managed by a European

forester and 50-180 Africans, with a Forest Officer in charge. Of the 34000

acres so far planted the principal species are Patula with up to 20% of

Elliottii and Taeda pine, and nearly 2000 acres of eucalypts, and a further 3

000 acres will be planted when all the suitable land is in production. The

purchase of further land extended Charter boundaries, and a slow consolidation

has resulted in a single large holding today of 45000 acres in the upper Nyahode

catchment, with Welgelegen a separate 6500 acres, and the Chartered Company is

the largest private timber grower in the country.

About $4 million has been invested, of which some $2,200,000 represents

plantations, and at maturity this figure will have risen to $8 to $10 million as

conventional sawmills keep pace with timber yields. The mill at Fairfield

processes three quarters, rising to one and a

quarter million cubic feet log input yearly derived principally from

thinnings; it yields mainly boxwood and the better processed building lumber

will follow in increasing proportion as the forests become older; and plans are

well advanced for sawmill stages advancing to two million cubes input by 1971,

and later to 7-8 million.

The General Manager of the autonomous Eastern Forest Estates directs forest

activity, and Charter has a staff of 18 Europeans, with the foresters supported

by a technical and administrative headquarter unit. 670 Africans are employed,

of whom 100, under three Europeans, run the sawmill. In 1965 the B.S.A. Co.

amalgamated with two mining financial companies and became Charter Consolidated,

and shortly afterwards Charter Forest Estates with other interests in Rhodesia

were sold to Anglo-American who are today responsible for control and

finance.

Tilbury Estate is a hive of activity and has a population of 12

European families and 560 African employees.

Gwendingwe Estate is divided into four sections each with its own

labour force, machines and headquarters: Headquarters section under the Manager

consists of administration, workshop, maintenance, repairs, houses and water

supplies; Brackenbury is self-sufficient under the Farm Manager and assistant;

Forestry has a Forest Manager and assistant; and the Orchard Manager runs his

section with his assistant. About 5 500 acres of pines, 1 000 acres of wattle,

and 200 acres of gums have been planted, and further planting is continuing.

In round figures 300 acres a year are felled and 400 planted, so that the

plantation will come into a sustained yield with the same number of trees being

felled and planted after 20 years, after which capital charges become

impossible; enormously heavy logs cost more to log; and with the trend towards

reconstituted board, finger-jointing and lamination, large diameters are not

desirable. With 17-year old trees logs are quite often 20� long with a 14� or

15� tip, and are difficult to handle especially in steep country.

Through the dry season two Europeans and about 50 Africans are on

standby fire duty, and the crews of the fire vehicles are on duty all the time:

they have their own compound and are always there, always familiar with the

routine, and always trained. To compensate for their long spell on duty they are

given two months� paid leave in the wet season, and seem very happy with the

arrangement.

Gwendingwe employs, with seasonal fluctuations, between 350 and 400,

and with their families the African population is between 600 and 800, and the

development of the compounds in the form of African villages is encouraged. Each

Section�s bossboy is the village headman and has the responsibility of seeing

that village life is organised on traditional lines and that the disciplines

which would guide their lives at home are observed.

The labourers tend to group into tribal or family groups, and go to work

with their own bossboy whose position is gradually enhanced as he grows older

and the younger men, who were children under him, come into his gang. This

system is working very well, and there is much visiting between the villages and

inter-village competition in sports and other activities.

The housing is round brick huts, cement-floored, and a family unit is

two living-huts and a kitchen-hut; a unit may also be occupied by four

bachelors, two sharing each of the living-huts, and cooking communally. Pay is

given in lieu of rations, but meat or fish is issued weekly. The trading store

is leased to outside interest. The Estate sells commercial African beer but has

not yet built a beerhall; no brewing is allowed, but the staff can buy as much

as they want: rather than all walking up to tbe centre, they usually send their

women along to bring back ten or twenty gallons to the village, where they then

have their own beerdrink.

The clinic is simply a casualty clearing station and ordinary clinic,

but has some facilities for inpatients with a female ward and some compound

units outside for men. The clinic has as a major aim a Family Planning campaign

and has plans for mothercraft and a wide range of child care and hygiene

training. It is supervised by Annabel Hayter who is a fully trained Sister, and

is run by an African nurse whose husband is a Public Health visitor based at

Gwendingwe and who also does public health work in Mutema Tribal Trust Land. A

tremendous number of patients come from Mutema, and as this is becoming a

problem a small fee may have to be charged.

There are about 90 pupils in the school, for which Gwendingwe Estate

supplies and maintains the buildings and pays for the equipment. The Government

pays the teachers and the school is supervised by Rusitu Mission. Education up

to Grade Five for the families of all employees is entirely free.