The Martin trek reached Waterfall on 17th October, where they learned

that Thomas Moodie had recently died. They spent a few days with Mrs. Moodie,

then most of them carried on towards the Chimanimani area which Marthinus Martin

had chosen the previous year on his exploratory trip.

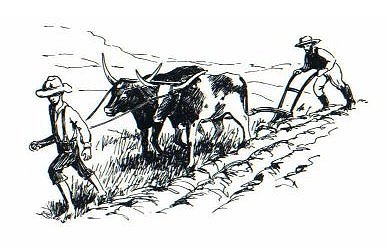

A big problem was how to get the wagons to their destination. The big mountains north of Sterkstroom and the Rusitu river rose as if they were out to prevent even the bravest and most dauntless trekker from proceeding one step further, but they were determined to reach the chosen goal. Reconnaissance parties found a way, and so they carried on slowly, down the Rusitu valley and up to the top of Uitkyk, where Mrs. Scholtz, who was respected by all and whose death was a severe loss, was buried. They travelled down to Albany, through the Nyahode river at Bloemhof, and up over towards Orange Grove. Here there was a hitch when a police officer, Joe Nesbitt, suddenly made his appearance with a letter from Dunbar Moodie commandeering all the men to come with their rifles and ammunition and provisions for eight days to withstand a Portuguese army which planned to take over Gazaland. All the men except Martin, Olwage and Heyns went off to Kenilworth in pouring rain. After eight days they arrived back at the Trek, wet, hungry and tired, and without having had the privilege of meeting with the Portuguese. On 3rd November the Trek arrived at Lindley, and after a few days there each said farewell to his fellow-trekkers to settle on the farm of his choice. The whole party was deeply grateful to Marthinus Martin for the way he had led them and had shouldered the responsibility. The Martin Trekkers were unfortunate, as the Moodies had also been the previous year, that the trek had taken very much longer than had been anticipated. Arriving in November meant that they were late for planting food crops, and November and December that year were very wet. However, they ploughed as much ground as they could, planted all the seeds they had brought with them, and were encouraged at the satisfactory rate of growth of the maize and vegetables. Martin hoped others would move to this area, which had a plentiful supply

of water, an ideal climate, wood in abundance, and grass admirably suited for

cattle and sheep and probably for horses; he said that he was completely

satisfied, although a pioneer�s life was no easy one.

They had little contact with the outside world, but their health was good, and they settled down with determination. They were firm, stout-hearted, deeply religious people, ready to stick out the initial hardships in order to make settled happy homes in this wonderful country. Their first buildings, which had to do duty for years, were huts in the native style: a circle of poles planted close together and plastered with mud inside and out, with a thatched conical roof. These rondavels, or pole-and-dagga huts, were used for dwellings and administrative offices. Those who have experienced some of Melsetter�s heavy rainy seasons can dimly appreciate what the conditions must have been like: living in their wagons, which were surely by then not as weatherproof as when they set out from the dry Free State; huts being slowly built in the rain; no fireplaces for drying those eternally wet clothes; all leatherware and many other articles covered with green mould; cooking out of doors whatever the weather; looking after the small children, while the older ones worked outdoors; doing the ploughing and planting themselves with little or no outside help.   By April few families had any flour left and their vegetable supplies were

meagre; they eked out what they had with pumpkins and mealies in place of bread

and honey instead of sugar. Their staple diet was rapoko (a small grain) meal

bartered from local tribesmen for such clothes and material as could be spared.

Sewing needles were very precious, and replacing their own clothing was a

serious problem and they had to start using tent canvas as a source of cloth.

Fortunately buck were plentiful, so they could get meat and hides, but

ammunition was short and had to be used sparingly: youngsters soon learned to

get a buck with each shot, as they were not allowed to waste a single

round. By April few families had any flour left and their vegetable supplies were

meagre; they eked out what they had with pumpkins and mealies in place of bread

and honey instead of sugar. Their staple diet was rapoko (a small grain) meal

bartered from local tribesmen for such clothes and material as could be spared.

Sewing needles were very precious, and replacing their own clothing was a

serious problem and they had to start using tent canvas as a source of cloth.

Fortunately buck were plentiful, so they could get meat and hides, but

ammunition was short and had to be used sparingly: youngsters soon learned to

get a buck with each shot, as they were not allowed to waste a single

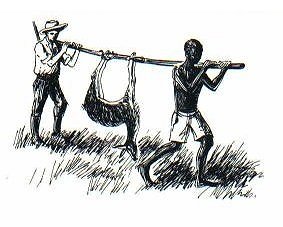

round.The railway line from Beira towards Umtali had by then reached

Chimoio, from where supplies were obtained by carriers. From the outset Dunbar

Moodie pressed for the Company to build the Umtali-Melsetter wagon road. He

stressed that it was a matter of great importance as the settlers needed roads

to travel on.

In January 1895 Mansergh, the surveyor in charge of the Beira railway,

surveyed and started laying a road between Umtali and Melsetter, and by June

wagons could get through although the journey took many weeks, and for a few

years transport was also carried on the less mountainous but less healthy route

through the Chimanimani Gorge to railhead at Chimoio.

The district was administered from the B.S.A. Company headquarters on Dunbar Moodie�s farm Kenilworth, where pole-and-dagga huts were the Government offices and a police force of thirteen was stationed. From 1893 Dunbar was what he himself termed Pooh Bah: Native Commissioner, Justice of the Peace, Magistrate and Administrator of Gazaland. He was also Postal agent, and each quarter a relay of runners carried

despatches and post; the runners could reach Umtali in three days in favourable

weather, but with the erratic service letters from Salisbury were often answered

from Kenilworth many weeks later.

In 1895 administrative changes were decided on, Dunbar was relieved of his official appointments, and 1. P. Heugh was appointed Civil Commissioner and Resident Magistrate. He was welcomed in the following terms from Rocklands: �We the undersigned residents and burghers of Melsetter District of Gazaland tender you a hearty welcome to your new sphere of duty. Heugh took up his duties at Kenilworth, where he was assisted by a clerk, and from the outset he and Dunbar were at loggerheads. He asked for an inspector of farms as he found that the confusion through Moodie�s maladministration was so great that it was difficult to apportion out the country according to recognised rules. Moodie rendered no assistance, and people were flocking into the country quite in numbers. Under the Certificate of Right 3,000 morgen could be allotted, but in many instances double and treble that had been taken, and wherever one went it was said that the ground belonged to some Moodie or other. Heugh investigated the allegation that Moodie had in several instances

received considerable sums of money for selling ground belonging to the Company,

as he felt that the man was quite capable of selling the whole country. He urged

the appointment of an inspector as the last confusion would be greater than the

first if this were not done, and suggested a salary of �1 per day with the

necessary means of locomotion, say two horses.

Dunbar had by then had 4000 morgen surveyed in excess of his grant of 27 000 morgen and instructed J. M. Orpen, who was working on the district survey, to survey a further block for him. He had also charged high fees for checking beacons for settlers and some farmers had to leave as they were unable to meet these unreasonable demands. In August Heugh reported the utmost difficulty in taking over from Dunbar: he was obliged to use force in obtaining from him what Government property he possessed, and was afraid it would be hopeless to try to get details of his transactions. During 1895 Martin reminded the Rev. Andrew Murray of his earlier request that the Gazaland settlers should have a Dutch Reformed Church Minister, and in response to the Synod�s call the Rev. P. A. Strasheim travelled to Rhodesia, formally constituted the Melsetter Congregation on 12th October, and promised that a Minister would be sent. A few months later the Rev. P. L. le Roux arrived to take on the spiritual and educational care of the residents of the scattered parish of Chipinga, Melsetter and Cashel: occasionally he also had to visit parishioners at Inyanga.  For the next eight years he worked untiringly on behalf of the community,

on whom he had a profound influence.The centre of the settlement gradually

become definitely the Chimanimani area, closely filled by the Martin Trek, and

the feeling grew that the township should be established there. The original

idea was to move the township only, but somehow the name came with the move, and

the towniands to the south, which had been pegged out but not developed, became

Chipinga. For the next eight years he worked untiringly on behalf of the community,

on whom he had a profound influence.The centre of the settlement gradually

become definitely the Chimanimani area, closely filled by the Martin Trek, and

the feeling grew that the township should be established there. The original

idea was to move the township only, but somehow the name came with the move, and

the towniands to the south, which had been pegged out but not developed, became

Chipinga. The few Moodie trekkers who were still there disliked the fact that the

name Melsetter was being taken from them, but they were outnumbered and their

spokesman, Dunbar, had quarrelled with the magistrate. After consideration of

various sites on Rocklands, Cecilton and Fairfield, G. F. Heyns� farm Dunbarton

was chosen, and J. F. Markham was employed to build the necessary huts.

On 3rd or 5th September 1895 (the exact date is indecipherable in the original letter) Heugh wrote that he had concluded negotiations with Heyns for the transfer of Dunbarton to the Government, in lieu of which he was to receive the farm Fairfield on the Nyahode river. Some difficulty was experienced because in April, when the idea was mooted of placing a township in that vicinity, Dunbar Moodie immediately beaconed off these farms for his own benefit and appropriated the ground without having any legal right to it and said that he would question anyone�s right to interfere with his distribution.  A few days later the Administrator removed Heugh from his post as his

administration had not been satisfactory: he had had no training to fit him for

the responsibilities, besides his quarrel with Dunbar there was friction with

other farmers who petitioned for his removal, and he was reported to have

carried on in a way which was a disgrace to the service. Following Heugh�s

sudden departure Inspector R. C. Nesbitt took over as Ading C.C. and R.M. A

glimpse of administration is caught in a requisition from Inspector Nesbitt,

presumably in his Police capacity, for two cats of nine tails, which he hoped

would be forwarded by return of mail. A few days later the Administrator removed Heugh from his post as his

administration had not been satisfactory: he had had no training to fit him for

the responsibilities, besides his quarrel with Dunbar there was friction with

other farmers who petitioned for his removal, and he was reported to have

carried on in a way which was a disgrace to the service. Following Heugh�s

sudden departure Inspector R. C. Nesbitt took over as Ading C.C. and R.M. A

glimpse of administration is caught in a requisition from Inspector Nesbitt,

presumably in his Police capacity, for two cats of nine tails, which he hoped

would be forwarded by return of mail.~~~000~~~ |