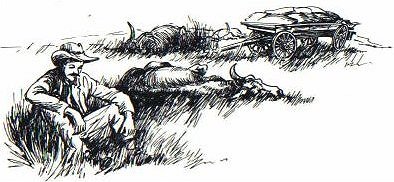

Melsetter was nearly drawn into international affairs when Paul Kruger tried to persuade the Portuguese Government to arrest Rhodes on his arrival in Beira and to take him to Melsetter where the Transvaal authorities would be ready to take charge of him, but the Portuguese authorities would have nothing to do with the scheme.  The first eighteen months had been one long struggle, with little food, no

cash, difficulties of marketing any saleable surplus, and all capital locked up

mainly in cattle, but at the beginning of 1896 prospects were good and the

outlook was bright. Against the background of hopes and difficulties two events

started during the year which set back the smooth development: Rinderpest and

the fears of a native rising. The first eighteen months had been one long struggle, with little food, no

cash, difficulties of marketing any saleable surplus, and all capital locked up

mainly in cattle, but at the beginning of 1896 prospects were good and the

outlook was bright. Against the background of hopes and difficulties two events

started during the year which set back the smooth development: Rinderpest and

the fears of a native rising.The beneficial occupation clause was difficult to fulfil while farms were not producing a livelihood, and many farmers left their wives to carry on farming operations while they undertook the long trek away from Melsetter with their wagons and oxen to earn money in transport work. The result was that the devastating scourge of Rinderpest hit them very hard indeed. The disease crossed the Zambezi into Rhodesia in February 1896; the spread was rapid with infection carried by game, and the whole country was swiftly affected. Little was known about prevention or cure of the disease, and many Melsetter farmers lost so many cattle that they were forced to give in and move away, abandoning any progress they had been able to make on their farms. Such oxen as survived were at a premium, and transport charges soared, which was another hazard for those who remained in a district so dependent on ox transport. Food was very short, and Government supplies of rice, bully beef, tea and other necessities were sent up by donkey wagon and were rationed out each week in the township. In June the Farmers� Association expressed its thanks for what had been done to alleviate the position. In July Henry Sawerthal, in charge of Company transport between Beira and Salisbury, sent out an official notice commandeering all trek oxen belonging to farmers in the Melsetter district for the transport of food supplies from Chimoio to Salisbury. All the farmers whose cattle were purchased considered themselves very well paid, except Dunbar Moodie, who waited for three months and then complained that he had not received enough money for his .

In order to get supplies to Melsetter some highly impracticable proposals were suggested from Salisbury. One was that oxwagons should leave from Gazaland in order to return with food, and Sawerthal commented that such a modus operandi would devastate the district by rinderpest. Then it was suggested that wagons should come from Fort Victoria to the western bank of the Sabi, from where supplies would be carried across the river and taken to Melsetter either by carriers or by wagons sent down to the east bank. Efforts were made to get donkeys or mules to replace oxen, but these were at a premium. Carriers were sent from Melsetter to load up with requirements at Chimoio, where there were plenty of provisions. In May Dunbar wrote that farmers near him were uneasy about the Matabele disturbance, and he felt that something should be done to allay any fears, although he did not think that any public demonstration would be wise as the natives were quiet but might rebel if there were signs of fear or misgivings on the part of the settlers. The FA. June meeting resolved that if farmers heard or saw anything definite to excite suspicions relative to the rising of natives they should report at once to Longden, and asked that spies should be placed on the district border as a precaution against a rising, and recommended that Melsetter township be the site for a laager in case it became necessary to form one.  Anxiety mounted among the scattered farming populace, and Steyn and

others from Cashel moved into larger at Elandspruit on Rocklands. This took

Martin by surprise: Steyn said that they had been advised to gather in one

spot as danger was near and a rising feared, but when Longden reassured

him he said that they would be happy to return to their homes. Anxiety mounted among the scattered farming populace, and Steyn and

others from Cashel moved into larger at Elandspruit on Rocklands. This took

Martin by surprise: Steyn said that they had been advised to gather in one

spot as danger was near and a rising feared, but when Longden reassured

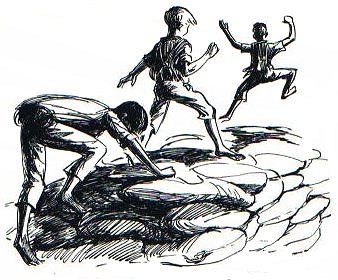

him he said that they would be happy to return to their homes.Longden was supplied with 50 rifles and 25 000 rounds, and a volunteer Burgher force was organised and troops were stationed in Umtali, from where the Postmaster kept Longden informed of news from other parts of the country. Martin was worried about reports about the war: losses in the Matopo Hills, murders in Mazoe, rising in Fort Victoria; and he asked Longden whether it would not be advisable, if they were true, that all available forces should be concentrated. On Westward Ho! Markham built an underground tunnel as an escape route from

his house.

A public meeting in August discussed the position. Twenty-five attended, Longden was the Chairman, and J. T. English reported that the Chairman most ably put forward his ideas and asked the settlers to express their views and to decide whether they would take precautionary measures to ensure their safety. A proposal by Cashel farmers, that outlying farmers should concentrate and form camps, was carried by a majority of 15 votes; and an amendment by Melsetter farmers was defeated, that no steps be taken and farmers remain as they were. Sawerthal wrote to Longden, wondering who had alarmed the Melsetter people, and Umtali Postmaster said that there had been disquieting rumours about the Melsetter people being forced to go into laager. There is no evidence that Melsetter went into laager in 1896, but the anxiety carried on and flared up again in 1897, and after a residents� meeting in August Claude Orpen told Longden that he had been unanimously elected Commandant of the central laager, and arrangements were made for the camp to be formed. Longden made a fort, six or eight feet high, with 200-lb mealie bags filled with sand and piled on top of another, with no cover on top; the children enjoyed having their playhouse during the day on these sandbags. Chipinga farmers could not travel to Melsetter as they had no span of oxen which could bring a load, and Gifford wrote that they would try to get together at Wolverhampton. The Umtali C.C. sent a Police Officer with twenty mounted men who escorted nine Melsetter people, of whom four were on Company horses which on arrival were to be given to the police. In order to send the reinforcaments he had reduced the Umtali police to four, with no horses, and felt that he could not safely reduce the strength further as if Melsetter natives rebelled the Umtali ones would be very doubtful. He asked Longden to send a full report with details of what supplies were most urgently needed, and promised to send a pagamesa train (carriers with loads on their heads) with the requirements, but said than an escort would be difficult to arrange for the wagons which were ready loaded to travel as the journey would take ten days and nobody knew if it were safe to use the road. There was no further cause for alarm, and after being in laager for two or three weeks people dispersed to their homes. Longden was thanked for his reports; the Acting Administrator expressed his satisfaction that the prompt measures taken were successful in averting trouble; and Melsetter residents wrote to Longden expressing their thanks and appreciation for all that he had done. An interesting side light on these times of tension occurred when Henry du Bourg Bancroft Espeut, a Moodie Trekker and the first owner of Albany (Whose name is incorrectly spelt Ashpute in many records and on the Pioneer Memorial) left Chimoio with twelve carriers, some dynamite and tools, and seven sick Company mules which it was hoped would regain strength on the excellent Melsetter grass. He travelled with a Melsetter policeman, Kleinboy Faan, who was accompanying bearers bringing supplies. Espeut was carried through the first rivers by boys, but when they reached

the Chimanimani Gorge he walked through the Msapa river with his boots and socks

on, and did not take them off until after dark. After supper he called the

policeman and said that he had a stomachache and had been poisoned by the

bully-beef he had eaten. He was very ill that night and the next day, and in the

evening Grotwahl, a local farmer, arrived at the camp and saw him shortly before

he died.

Grotwahl examined the remaining bullybeef in the tin and found it quite

fresh. Sergeant W. F. Moss of the Melsetter Mounted Police was sent out and

Espeut was buried on Rocklands. At the inquest Longden found that the Court was

of opinion that death was from natural causes: although Espeut had thought he

had been poisoned by the tin of beef, nothing confirmed that supposition, and

the evidence led to the conclusion that death was caused by an acute attack of

colic probably brought on by wet feet.

~~~000~~~ |