The possibility of erecting a Pioneer Memorial was frequently

discussed, and the Rhodes Trustees were approached for the donation which Rhodes

had promised and Longden described the form Rhodes had wished the memorial to

take, but the Trustees replied that, had Rhodes lived he would doubtless have

fulfilled any promises he made, they had to abide by the terms expressed in his

will. As no money was available the project had to be shelved.

Louis Ferreira was for many years C.C.�s clerk and Court Interpreter,

and lived with his wife Alice (Cannell) in the cottage �Bethany�, which he

built.

A temporary gaol hospital was built with prison labour and a house for

the gaoler was built for �450 about where the W.I. Hall is today: he had until

then lived in a very dilapidated pole and thatch structure. Remmer as gaoler had

two warders under him, but as Sergeant of Municipal Police he had no force, and

Longden pressed for police supervision in the town if only to prevent the

contamination of the water supply.

During Reminer�s absence on leave a relief gaoler came from Umtali, who

sent a bandit (as convicts in Rhodesia are frequently called), to the village

with a message, with the solemn injunction that if he were not back by 9 p.m. he

would be locked out! The gaoler also upon occasion gave the keys to the bandits,

with instructions to rescue him at a certain hour from his night out. The end of

his service came at a later date in Umtali when he was wheeled, fast asleep,

through Main Street in a wheelbarrow while one bandit shouldered his gun.

Football was a popular pastime and a regular feature of Nachtmaal

weekends. At first it was soccer, later rugger, played �ijust below the village

green, and enjoyed by both spectators and players. John Martin was the Country

goalkeeper in matches against the Town, and wore khaki trousers, braces, necktie

and a belt; Alfred Gifford wore a pair of three-quarter trousers, and Oxenham,

Andries Bezuidenhout, Antonie, Frans Steyn and Andries Kok were among the

forwards and wore shirts, over which they pulled black, coloured or striped

vests.

The Rifle Club complained that most erratic shooting had resulted

because the rifles forwarded were old and worn-out and the ammunition obtained

through the Officer commanding the local Police was bad. The first consignment

of ammo had been cordite of good quality, but latterly they had only had very

old cartridges loaded with pellet powder: cartridge cases in most instances

burst, very often the butt end was blown off with the case remaining in the

barrel, and on one occasion the magazine of a rifle was blown clean out. The

Club asked that it should be conceded the same privileges allowed to others, and

be supplied with suitable rifles and good cordite ammunition. Some months later

ammunition and new rifles were received, the Government grant was devoted to

making a new range with improved up-to-date targets, and practice was

resumed.

The Farmers� Association was granted permission to hold stock fairs

without taking out an auctioneer�s licence or the payment of auction duty, and

the Administrator approved of two stands being granted to the Association for

the erection of a suitable building but there is no record that any move was

made to follow up the offer. Some cases of rabies occurred during the

year.

The Merino experiment had not been quite equal to expectations but had

proved that a large part of the country was suitable for the production of

woolled sheep. Sheep on highveld farms had done very well, but those on

low-lying farms were much troubled by malarial catarrhal fever � bluetongue �

and the mortality was senous. When losses continued the Rhodes� Estate was asked

to bear the expense of importing sufficient serum to inoculate the sheep for

farmers who could not afford the outlay, but said that it was not possible. Some

of the original recipients found that they could not carry on and there was a

certain amount of switching of ownership; Dr. Rose took over some and ran

Merinos on Lemon Kop for over 40 years.

At the School parents still had difficulty in paying boarding fees: one

term two parents only paid the �2.10 for their own children, and fees were

either paid by friends or the school was obliged to take in supplies, in some

cases at a loss. Miss Gilson tried hard to raise money for the school, and when

on leave in England and America she appealed to friends for funds. Her success

in this effort is not known, but her appeal to the Rhodes Trust resulted in a

cheque for �50 after much correspondence, accompanied by the warning that it was

to be clearly understood that the Trustees were not likely to repeat the grant

or to send the school further assistance.

By 1906 tuition fees were payable by parents: if there were three

children from one family at school, the third paid half tuition fees, and if

more than three the three eldest paid full fees and the rest were admitted

free.

Mary

Ward came to teach at the school and found it �working under

serious disadvantages, of which the most important is lack of proper

accommodation. Like most Melsetter houses ours has mud floors smeared with cow

manure, which sounds rather dreadful, but it soon dries and we put down reed

mats and think nothing of it. Some people have linoleum, but we cannot afford

such a luxury. I have a carpet on top of my mats, and in the diningroom we have

coconut matting. The houses have zinc roofs and we have great difficulty in

keeping out the rain, but you soon get used to the drawbacks and learn to take

everything philosophically.

�The girls sleep in a big dormitory and my room is partitioned off from

this. I boast a calico ceiling, but they have only rafters and zinc. The boys

sleep in two small rented brick houses. The diningroom and sitting room are in

yet another building, and we can just fit into the diningroom with our 20

boarders.

�The Minister is very anxious to have a Dutch teacher in the school,

but as the Government will not allow Dutch to be taught during regular school

hours it is a difficult question, and we have nowhere to put another teacher

even if we could support one. Another lady is coming with Miss Gilson, so we

shall be three instead of two.�

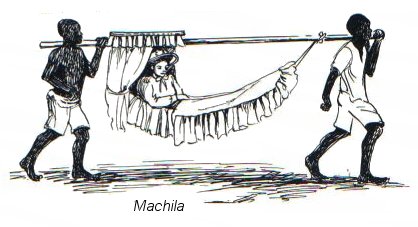

In November the school broke up a week early on account of a case of

measles. Special messengers were sent out to tell parents to fetch their

children, and they all went within a few days except for one little American

girl from Mount Silinda, who had to wait for her father to fetch her and who

would then be carried home in a machila.

Describing her journey to Melsetter Mary Ward wrote that �At 8 a.m. I

left the hotel at Umtali and, escorted by two natives bearing my small baggage

and supplies on a small handcart, I walked about a mile to the outspan. The

driver introduced me to my fellow traveller on the wagon, an unshaven and rather

objectionable man.

�Rather more than one third of the wagon was covered with a tent, and

my mattress was placed under this on top of bags of flour, etc., which made my

bed full of ups and downs. It was impossible to sleep while trekking, but we

always outspanned for an hour or two before dawn which made a most welcome rest.

We had a large train of natives:

I had two boys, the driver two or three, and

the other man had four, not counting the piccanins.

�I cooked my breakfast of bacon and tomatoes. The other traveller made

scones of flour and baking-powder which he cooked in a fryingpan. He asked me to

try one, and though I knew his hands would have been improved with a wash, 1

accepted and enjoyed it.

�The scene was peaceful and beautiful and the scenery grew more

picturesque, but the road, winding between high rocky kopjes, grew worse and

worse. I walked when I could, but one evening I found out what a real rough

shaking is. First it seemed I was going head first through the tent over the

load into the river: then as if I was about to slide into it feet foremost, and

had great difficulty in keeping my feet from going through the mosquito-netting

which closed the opening of my tent. There followed such a shaking up that it

made me feel as if every organ and bone in my body was playing at general post,

together with a painful sensation as if a giant had taken me up to wring me out

with a particularly tight twist round my waist.

�One late afternoon I walked ahead with two Police boys, one armed with

a gun. We picked up friends by the way, and after a mile or two I found myself

alone with twelve natives: it seemed very strange to be walking through

nine-foot high elephant grass in the dark in their company. Once they all

stopped and began talking, wondering how I could cross a stream. I made them

stand aside and I jumped and managed to escape with one small splash, whereat

they all laughed cheerfully. As the stars came out my spirits rose because I

could see the Plough and Orion which my friends at home could also see. The

reeds grew very high, and dozens of fireflies were sailing about them in a

gentle fascinating way. We came to the outspan, where the boys lit big fires and

we waited for the wagon and oxen to come up.

�Another evening I walked to the first Nyanyadzi drift: with the help

of a knobkerrie, a kind of heavy walkingstick, and the assistance of a Police

boy, I got over dry. At Pritchard�s store, a few buildings of wattle and daub in

a wire fence enclosure, dogs flew out to greet us and the owner appeared with a

lantern and led us inside.

�We then crossed the Nyanyadzi seventeen times! It winds down a narrow

valley, and we crossed it three times in a quarter of an hour. Travelling by

wagon is no joke: in congenial company a trek of two or three days might be

delightful, but I have had enough. My trek was a good one, that is, we made it

in just eight days. Sometimes it takes ten or twelve and, if there are heavy

rains and floods, as much as three weeks.

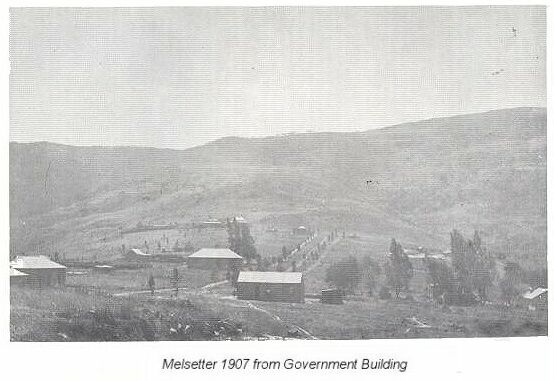

�Melsetter township consists of about 15 buildings including the Court

House and a few huts. It is found in the NEWEST atlases, and we consider it a

most superior place: surrounded by hills and facing the Chimanimani Mountains

the situation is very picturesque. Not counting the boarders, there are about 26

white people, with most of the men in Government service. It is a sociable

little community and I am very happy here.�

Mary Ward camped with friends in an unoccupied farmhouse about six

miles out. The men walked and the ladies rode donkeys, which caused Mary some

anxious moments: she did not find it easy riding on a lady�s saddle on a small

donkey, but later found it more comfortable to use a man�s saddle on a large

donkey, with the right stirrup brought across to the left for a sidesaddle. In

the tumbledown house, with no doors between the rooms and no glass in the

windows, they picnicked very gaily. Their diningtable was a board resting on

stones, which was used only in the evening, all the other meals being taken on

the ground under the trees. Native boys carried out deckchairs, cushions and

blankets, and those who did not like making beds out of deckchairs had grass cut

and slept on the floor. Every morning the men went out early to shoot and came

back about 10, when they all had breakfast, and went out together in the

afternoons and thoroughly enjoyed the mountain walks and glorious scenery.

Mary�s next expedition was climbing the Chimanimanis. She and Mr. and

Mrs. Roberts and two other men walked out to Rocklands and set out the following

morning. �I chose the lowest and slowest mount, Esau the Dutch Church donkey

borrowed for the occasion but, as he is given to shying, I was advised to take

Long Legs. The mountains rose up straight before us, but we had to make many a

long detour before we reached the top. The morning was glorious and we rode

along through beautiful country. When we camped for breakfast one of the party

produced some bottles of Ross�s Belfast Ginger Ale, such an odd commodity to be

sold at the store in Melsetter.

�Up the rocky gorge the animals had to be led, and to add to the

difficulty of climbing the whole place was covered with brushwood blackened by a

grass fire. We rode again when we came to open country and then had to dismount

again where the footpath was very narrow and broken � if the animals had

slipped, we should have rolled many feet below.

�About 4 p.m. we entered a beautiful valley through which wound a

peaceful river, and on all sides rose the topmost peaks. We made our camp among

a huge group of rocks and had our lunch-supper-dinner. While the men went off to

shoot, Mrs. Roberts and I retired to a secluded pan of the river and performed

an extensive if not elaborate toilet, while the baboons barked most angrily.

Game was scarce and only two duiker were seen all the way.

�We sang and chatted in the starlight before we retired. Mrs. Roberts

and I shared a small tent and the men slept in the open.

�At 6 a.m. we rode to the bottom of the peak which we were to climb,

where we left the animals to graze and continued on foot, by now in Portuguese

territory. The climb was easy and near the top we came to a most glorious view

with a bank of cloud in the distance. We cheerfully continued to the top, but

alas, the mist had rolled up and we could not see more than a yard in front of

us. We each added a stone to the beacon and then descended. I was tired when I

came down, but I revived sufficiently to enjoy the walk and ride back to

Rocklands, where we spent the night, and next day we all walked back to

Melsetter.

�Now I look at the Chimanimanis with pride as well as pleasure. Mrs.

Roberts and I are the first ladies who have ever climbed these mountains; at any

rate no one here has heard of any other women, white or black, who have

attempted what we did.� Mary married George Rose in 1907.