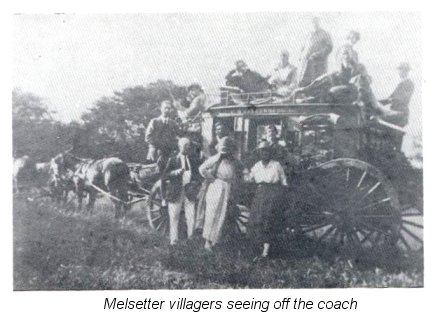

Marie, daughter of H. D. Martin (Mrs. Hack), left Melsetter for school

in Bulawayo. The night before they left it rained steadily, but the morning

dawned fair and, with servants carrying her scoff box and tin trunk, she went to

the market square to board the coach. Nearly all the villagers were there as the

weekly arrival and departure of the mail-coach was a big event, not lightly to

be missed. Six passengers could be carried in two rows of three facing one

another with knees almost touching, but as there were only four Marie, Connie

McLeod, Mr. Lenthall and a Post & Telegraphs technician � they travelled in

great style and comfort. Luggage and mailbags were secured to the back of the

coach and covered by a tarpaulin. Final goodbyes were said, they took their

places, the Cape coachman mounted his high seat, his assistant leapt up beside

him, and with whip cracks, the clatter of hooves and a blast from the bugle,

they were off.

The team was fresh and the pace brisk as the coach rounded the shoulder

of Pork Pie and past Rocklands. Then came the long, heavy pull up and yet up,

till the nervous preferred not to look outside to the awful depths below.

Rounding sharp bends the leading mules had to keep to the extreme edge of the

narrow road, and clods flung up by their hooves dropped sickeningly out of

sight. On and on, then down the impossibly steep pass at Komiek Nek, round to

Steynsbank and a fresh team of mules, and an opportunity of stretching legs and

having tea and a bite. The new team had a long haul up and round to Rutherfurd�s

Hid, and then down the valley, across the Umvumvumvu, and on to the Half Way

huts where they spent the night.

The mountains, with very real hazards in those wet conditions, were

behind them, and ahead was comparatively uninteresting country, with minor ups

and downs though with large rivers to be forded. Next morning, due in Umtali

that afternoon, they were wakened by the bugle to a sodden world.

They found the Mpudzi river in flood, but after a short delay the water

appeared to have subsided, so the coachman said that with the fresh team ready

there they should be able to cross. With brakes locking the back wheels and

mules struggling to keep their feet on the slippery surface, the steep slope

down to the ford was negotiated. Halfway across the river disaster struck. A

wall of water swept through the coach, carrying downstream nearly all their

belongings and the helpless mules, hastily cut free by the quick-thinking

driver. One poor beast was drowned, but the others struggled to safety some

distance away.

There they were: four fare-paying passengers and two Zeederberg

employees, soaked to the skin and perched precariously on the rocking, teamless

coach in midstream. Connie, dressed incongruously in smart coat, new hat and

brown gloves, swam back, battling bravely through the waves.

Africans came from the coach stables and formed a human chain from bank

to coach, back along which they all struggled to safety. A fire was made and

they dried themselves as well as possible. The position was not good: nearly all

their belongings had gone, they had no food, and learned that return to

Melsetter was impossible as the road behind was cut by another stream, normally

a trickle but now a raging torrent. They got in touch with the Newnham family

who were camped close by and soon exhausted their limited food supplies. Before

the adventure was over they were eating crushed mealies kept at the coach

station for the mules.

The Post & Telegraphs man had saved a portable telephone from the

flood and climbed a telegraph pole, attached the instrument, and got news of

their plight to Melsetter. Elliot organised teams of bearers to bring food, but

they returned to report failure, and finally the Martins� faithful old servant,

Bye-and-Bye, managed to reach them with a box of supplies.

In order to rescue the Newnhams and the coach party the Umtali

Magistrate sent out a trolley and oxen for which, owing to A.C.F. restrictions,

a special permit had to be obtained, and also sent mealie-meal and flour for the

Overseer. The road was washed out in many places some ten and fifteen feet and

several landslides had blocked it, and all traffic was suspended.

In Umtali Marie was taken in by Mr. and Mrs. Jim English and was looked

after by their motherly housekeeper Miss Lettie Kloppers. The 100-mile journey

had taken a week instead of two days.

Marie had hoped that on reaching civilisation her troubles would be

over, but she was involved in a train accident near Rusape where a culvert had

been washed away. Eventually she reached Salisbury, was re-equipped by her

sister, and reached Eveline Girls� High weeks late, and her trunk reached the

school about a month later.

It was weeks before the next coach got through to Melsetter. The

carriers swam the flooded rivers with mailbags on their heads, and exchanged

bags halfway; letters only were carried, newspapers and parcels posted in

Salisbury in January reached Melsetter in April. Transport wagons were held up,

provisions became scarce, and drink ran out altogether; some residents suffered

badly from thirst and did not enjoy being teetotalers, and the first coach to

arrive bringing a cargo received a tremendous welcome.

During February the CC. telegraphed successive overnight high

rainfalls, and said that if it continued to rain as never before even runners

would not be able to get through. The roads were everywhere impassable for

vehicles, and it was useless spending money trying to mend them until the

weather cleared.

The official figures, from 1st November 1917 to 31st March 1918, were

94.25� in the township, which was less than in many other parts of the district.

There was serious mortality among stock as young cattle and donkeys died in

considerable numbers, and sheep and goats died in hundreds.

During March all official correspondence was carried out in very long

telegrams, and the C.C. appealed for a road engineer to come and direct

operations or tell him what to have done. Gangs worked on sections of the road

to make them passable, and the Overseer, again short of food and imprisoned

between unfordable spruits, dealt with severe damage.

By 16th April private conveyances had come through and the coach

service started again soon afterwards, but it was months before more than urgent

temporary repairs could be done to the road.

The road through Chipinga to Mount Silinda was a Government

responsibility, but it got little attention and was mostly in a shocking

condition. In 1918 a gang repaired some of the damage done at the beginning of

the year, and the Nyahode drift was descnbed as not being able to stand a

rainstorm as it had been built with very light material and had no batters

whatever.

Baboons were very troublesome, and hunts were arranged under the

control of the N.C., who supplied natives to help when necessary. Lee-Enfield

ammo was issued free, with unexpended rounds being returned to the N.C.;

ammunition for other rifles and for shotguns expended during a hunt was paid for

on application to the C.C.

A quantity of wool, several hundred bags of wheat,

and a little dairy produce were sent to market, but Melsetter was at the time

affected by the general depression after the War.

As there was a spell with no further deaths from A.C.F., farmers,

merchants and other residents urgently requested that the quarantine

restrictions be lifted to allow ox transport between Melsetter and Umtali.

Donkey transport was unobtainable, no mealies or grain for native food could be

bought locally, the farmers were asking prohibitive prices for wheat, and

necessaries for the European population were becoming scarce. Later in the year

restnctions were partly removed, and an Imperial Cold Storage buyer bought some

2000 head of stock.

In spite of drawbacks, advances took place in the village and

day-to-day life carried on. Lethbridge retired from the Police and took over the

house in which Meikles� Managers had lived (today�s Hotel cottage), and opened

the first fully licensed hotel, a great boon to travellers. Later several

bedrooms were added, and a large stable was erected capable of accommodating a

dozen horses.

The C.C. reported that a healthy sign was the erection of a large and

commodious store: the stone building which still stands sturdily today, built at

the instigation of John Meikle. Meikle Brothers had had a General Dealer�s

certificate since 1911, the first issued by the Melsetter Licensing Board. The

building of the store, supervised by a contractor, involved many residents: the

stones were laid by Daantjie Steyn, Stoffel and Schalk Kloppers, Tom Williams

and Barnie Marais, and the stones were lifted to the top of the wall by a small

crane. Karl Neeser did the carpentering with timber most of which Andnes Kok cut

in the Nyamarirwe valley in the Greenmount forest: after felling a tree, he

sawed it into 18� lengths and rolled each length onto the sawpit alongside, and

with the help of two boys got the pieces cut through, taking about three weeks

to cut one tree.

C. L. Mulling managed Meikles� Store assisted by George Gifford, who

also acted as Court Interpreter upon occasion. After Mulling came Fred Taylor,

later of Taylor & Nisbet and of Manchester Park, which he left to the

nation: today�s Vumba National Park. Carey Bland was the next manager.

There were small stores on many farms, and the other store in the

village was owned by F. E. Ctonwright. At that time Mr. and Mrs. Cronwright

lived at Jersey farm and his Melsetter store was managed by H. D. �Leggy�

Martin, no relation of the pioneer Martins, who was assisted by Mike Kok and

Abraham Olwage. The African side of

Cronwright�s business was run for many

years by Frans Majeji who farms today at Biriwiri T.T.L.

Store managers got �15 a month, with goods at trade prices. Farm

managers got �10 to �15 with house, free use of land required, a percentage of

increase and in some cases free riding horses. Farm labourers got 15/- a month,

cookboys 20/- to 30/-, houseboys and gardenboys 15/- to 20/-, all with food and

quarters.

Government officeboys and storekeepers drew 35/- a month and provided

their own rations. In 1920 the C.C. applied successfully for an increase of 5/-

a month for employees with a certain length of service, as all were married with

families, and a paraffin tin of meal cost 5/-, which was altogether beyond their

means. The cost of a prisoner had risen to about �45, with discipline over �28

and maintenance �16.

There was no butchery but game, especially bushbuck, was plentiful.

Chickens were 9d each from the natives. Farmers sold sheep for 30/- each, which

were killed and dressed by house servants; a meat saw and chopper were normal

kitchen equipment. Word was sent round when a farmer occasionally killed a young

ox, and the villagers went out to the farm and got a big piece of meat which

they then cut up as best they could; beef was such a treat that nobody minded

how far they went to get it.

Madge Elliot was glad to be taken on in the Office when Arthur Bill

joined the forces, as life was very dull for the young; social occasions were

rare but enjoyed by all when they did occur.

Mrs. Bertie Remmer was the character of the district, much loved and

very good to the young; all had a healthy respect for her too, and from the CC.

down everyone did what they were told very quickly when she talked. She objected

strongly to the imposition of wagon licences, and was highly incensed when her

wagon was impounded for not having a licence. However, when life got

particularly dull a young policeman would say: �Ma, what about a party?�

Mrs. Remmer always said: �Oh, you boys , but never said no, and to

the parties in her house the young all made their way on foot, carrying

hurricane lamps unless there was a moon, from the School, the Residency, the

Police Camp and from below the hotel. Music for dancing was provided by

concertina and mouthorgans and by Mrs. Remmer�s piano, played by young policemen

or by Mrs. Stanley who had been a music mistress or by the school teachers or

one of the others, as most could play a little. When Mrs. Remmer said: �That�s

enough now. Time to go home�, off they all went.

Her piano was borrowed for occasional dances organised by the War Fund

Committee, when it was carried to the Courthouse and back by the prisoners.

Everyone went to all the Olwage weddings and danced all night in a tiny little

room with the dust rising; their harmonium was used for hymns on Sunday and

dance music on other occasions.