At Nachtmaal

the village buzzed with

excitement for a few days. Farmers and their families came from far and wide,

bringing everything to make themselves comfortable: bedsteads, chairs, tables,

and even chests of drawers and sideboards. They drew up their wagons and pitched

their tents on vacant stands.

Religious services were held, and various committees met and the Young

People�s Debating Society held their meetings. In the evenings groups of people,

young and old, gathered round the campfires, singing to the concertina and

mouthorgan, telling stories, and generally enjoying themselves. Mrs. Elliott and

Madge called on each family, and were always received with great kindness and

genuine hospitality; they had everyone back to tea in their home, and made many

good friends in spite of the fact that a lot of the older people did not know a

word of English and the Elliotts knew no Afrikaans.

The highlight of the December Nachtmaal was a bazaar to raise funds for

the Church, and the townspeople were glad of the opportunity to stock up with

high quality supplies of bottled fruit, jams and konfyt, chutney and jellies,

delicious homemade bread and cakes, fruit, vegetables and needlework. The meat

stall always did a roaring trade:

boerewors, mutton, live sheep, ducks,

turkeys and beef were in great demand, and what could not be used immediately

was put into the brine tub.

The Elliotts had all visiting Government officials to stay with them

and also the Chipinga and Mount Silinda people on their way through. Even

Commandant Luon from Espungabera had to come through Melsetter to get to

Beira.

Scotchcarts with their high wheels, drawn by four spirited horses,

were useful over uneven terrain. The front seat across the cart normally sat

two, and behind the shared backrest there was another seat with the passengers facing

backwards � terribly sickmaking for those not accustomed to

it.

The children all had to help with household chores as soon as they were

old enough to be allotted tasks, but when those were done their life was

delightful and carefree, with few rules and regulations. The boys enjoyed

shooting with catapults or, if lucky enough, with a pellet gun, and there was

regular riding in the open countryside on donkeys, and occasionally there was

the delight of having a horse to ride. The young Koks visited their grandparents

at Belmont, two or more of them mounted on their horse Silver.

Memories include visits to Daantjie Steyn, the village cobbler, saddler

and dentist. A donkey ride to the dentist was unpleasant, with a cold head-on

wind agrravating the aching tooth; once the powerful Steyn had his young patient

in his grip there was no escape until the offending tooth was extracted, and

there were anxious moments while the patient watched carefully to see that the

correct implement was selected from the mixture of cobbling, leatherwork and

dental tools on the work-bench. Daantjie made good boots which lasted well but

imparted to the wearer�s feet an unmistakable smell from his home-tanned

leather: the children went barefoot during the week, but on Sundays their clothes included stockings and boots, which were

torture as they always seemed too

small.

Oom Gallie took Sunday School in High Dutch, and few of the children

found his services easy to understand. Those from outside rode in on donkeys and

changed into their tidy Sunday clothes in the gwasha near the Police Camp before

the service.

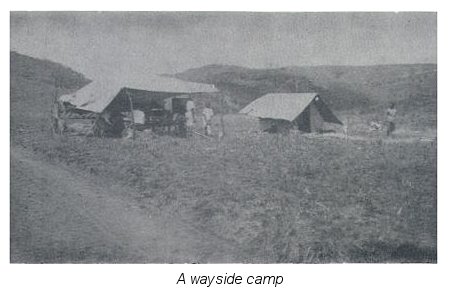

Camping trips were a joy. On one occasion John Martin took his family

and a party of others with four wagons down to the Sabi to trade. Two wagons had

half-tents in which the women slept while the men slept under the wagons. The

day started about 3 a.m. when the oxen were inspanned while the travellers had

hot coffee and rusks. The wagons jolted and squeaked over the rough tracks, and

memories recall the camp fires, the darkness with the wagons drawn up one behind

the other, the silhouettes of the oxen lying down tethered to the trek chains,

and the African drivers and voorleiers (piccanins who walked in front and led

the oxen) round their own fires.

During the 1914-1918 War Melsetter had an active War Fund Committee,

and impressive donations were made to a vast number of relief funds in Britain,

Rhodesia and other Allied countries. The Fund closed in August 1919 with the sum

of �573.4.2d in cash or value � items such as donations of 12 oxen are listed �

and it was decided to erect a small hail as a Memorial to those who fell in the

War.

When Spanish Influenza hit the area there was no doctor at Mount

Silinda so Dr. Rose�s territory was larger than usual: the epidemic struck in

many parts at the same time and of course all his practice was on horseback.

From the terse, mainly telegraphic, records, it is obvious that from June to

September 1919 he lived at absolutely full stretch.

In June a police telegram sent via Police, Umtali, reported 12 native

deaths. All public meetings were prohibited and church services postponed. By

23rd there had been further deaths at Silinda and 500 natives were sick in the

Chipinga area. Dr. Rose had attended 40 cases in the Rusitu area and arranged

for Howells at the Mission, assisted by two messengers, to attend to local

cases, and all natives at the Mission and many in the thickly populated Rusitu

valley had been inoculated. In Melsetter he had dealt with eight native and four

European cases. By the 27th one native had died at Melsetter and two more at

Silinda; 45 Europeans and 60 natives were ill at Melsetter and the position was

senous in Ngorima Reserve.

In July the schools were closed and had not re-opened by November. The

Government sent Dr. Gurney to help Dr. Rose at Chipinga, where in August there

were 27 European cases. One native died at Rocklands, 18 in Ngorima Reserve, and

five at Uitkyk. A cordon was established from 1st to 16th July, the natives on

the cordon being paid 8d a day.

Telegrams regarding the position flew backwards and forwards, and

needles, syringes and thousands of doses of vaccine were asked for. It was

difficult to get enough supplies, and the position was further complicated by a

Railway strike which prevented vaccine being despatched promptly. On-the-spot

reports were sent in by the N.C. as well as by the District Surgeon. By

September the outbreak had died down, and surplus vaccine was returned to

Salisbury.

That year cattle farmers had practically recovered from the heavy

losses from A.C.F., trade in livestock was carried on at good all-round prices

and hopes were high that A.C.F. was being eradicated.

H. Franklin was posted as Clerk in the Native Department, and Mrs.

Franklin with her two children travelled on the coach with Longden and Charlie

Remmer. The Franklins lived in a cottage consisting of two small rooms and an

outside kitchen next door to Ferguson. Weekly events were the arrival of the

Booze and Butter postcart and Leggy Martin�s auction of butter, eggs,

vegetables, poultry and other produce sent in by farmers. Dave Morris�s horses,

which were stabled in a grass shelter, were burned to death when early one

morning in winter the stableboy went to feed them carrying a lighted candle, and

the whole thing went up in flames. Dr. Rose was in Umlali on official business

when Mrs. Franklin�s baby was due, so when she felt it was time she walked over

to Mrs. Leggy Martin at Rose Cottage, about a mile away, where the baby was

born.

The most successful farm school was on F. W. S. Smith�s Springvale, and

with its establishment P. A. Cremer began his long association with Melsetter.

Later he married Lalie Steyn and took over and developed Johannesrust farm

school, today�s Cashel School. He and Mrs. Cremer live on Msapa today, with Mrs.

H. L. Steyn on Constantia a close neighbour.

Early in 1919 Condy rode out to Springvale with Stanley and discussed

with interested parents the opening of a school; arrangements were completed and

parents who shared in the erection were exempted from School Fees for one

year.

They built the schoolroom, 36� x 18�, with walls 10� high and a

thatched roof. They made the two windows and the door themselves as they found

the Government grant of �5 insufficient to buy sash windows at �7.10 each in

Umtali. Schalk Kloppers made the desks from local timber with a grant of up to

�15, and the furmture remained Government property.

Smith undertook to board the teacher at not more than �12 a quarter,

and a teacher�s room was built adjoining the schoolroom. It was unfinished when

the school opened, and when Cremer arrived he had to bear the cost of �5.15 for

materials for a ceiling which he put in himself, he bought four windowpanes at

4/3d each, and put in a floor of locally sawn planks. Later Condy said that the

schoolroom was neat and clean, and asked for an allowance for Cremer of 5/- a

month towards the cost of the boy employed by him at 10/- a month plus food, to

clean the school and look after his horse.

The school opened in September 1919 with 13 day-scholars and five

boarders: the building was not completed and the delay caused considerable

inconvenience, but with Cremer�s assistance it was gradually finished off. In

running the school from Sub Std. A through to Std VI, he steadily overcame the

difficulties of teaching children whose home language was Afrikaans and who had

had little or no previous education although many were in their teens. The

standard of attainment in English was much higher than Condy was accustomed to

find in schools of that type, and gradually the average age in each class became

satisfactory. An example of progress was a girl, aged 13 when she started in Sub

Std. A in July one year, who passed Std. V at the end of the following

year.

Numbers fluctuated in an unsatisfactory manner: in the first two years

31 came and went, with 18 the peak attendance and ten the lo\vest. The case of

Thomas Bosch was an example of how children were removed: he started school in

Sub Std. B, and two years later was in Std. V, able to take a creditable place

in Std. VI anywhere in Rhodesia, but was taken away from school to herd cattle

for the Tarka Ranch Manager in order to earn some money. At Condy�s request he

was sent back to school and was recommended for a free place at Melsetter

School.

John Kloppers was born in 1912 and went to Spnngvale School when he was

seven. It seems that he was not a model scholar, as his chief memory is of

having his backside lambasted with a quince stick, but he does appreciate the

fact that an effort was made to drill something into him. His memories include

much walking and the occasional donkey or horse rides in getting to school later

in Melsetter and in visiting his grandparents in Chipinga. When he went to

Umtali High they travelled in a lorry, and nobody minded if it got bogged down

on the way to school but it was a different matter when they were anxious to get

home as quickly as possible.

In 1919 Joey Grobler came to Melsetter to get married. George Gifford

met her at Weltevrede, and they rode over Sawerombi to The Residency, where she

spent the night with the Elliotts.

The Rhodesia Advertiser carried a full account of the very pretty

wedding, at which Elliott officiated in the specially decorated Courthouse. The

bride, who had endeared herself to children and grownups alike, was attired in a

pretty cream poplin costume with a white georgette hat, and carried a bouquet of

white roses. After the ceremony a reception was held in the Courthouse; the

presents were many, costly and useful, and included some substantial cheques. In

the evening a very enjoyable dance was given by Lethbridge and Gifford, with

attractive cosy corners tastefully arranged.

Some years before George Heyns had promised to lend his cart and horses

for this wedding. He had since died, but his widow remembered the promise, and

her son-in-law Solomon Potgieter had the cart ready after the reception. Joey

changed and Fred drove the cart while Potgieter followed on Fred�s horse until

Thornton, from where he drove back. Mrs. Delaney mounted a Zanzibar donkey

equipped with the bridegroom�s present of a saddle, and they set off along the

footpath to Willow Grove.

Fred managed Willow Grove and Fairview for John Meikle, who on occasion

came by coach to Melsetter, a horse was sent in for him, and the two men were

out on horseback every day checking the cattle as they wandered far and wide

right down to Cecilton as there were no fences. Leopards were troublesome and

Fred killed 59 during his seven years there.

Once he rode to Odzi with drovers to take delivery of some cows and

calves, while Mrs. Delaney stayed in Melsetter with the Mullings and the

Remmers. The trip took three weeks, longer than expected because the newborn

calves were too weak to walk long distances; there were delays waiting for

streams to go down; and Fred�s horse died of horsesickness, and he had to walk

with a boy carrying his saddle.

They stayed with the Oxden Willows on Gwendingwe, and Condy visited

them to see how a teacher had taken to farm life. Another visitor was George

Gordon, the D.V.S., who planned to leave early in the morning so goodbyes were

said overnight; in the morning the Delaneys heard him up early, walking up and

down the stoep, and Fred got

up to see if he wanted to speak to him again,

and found their seven dogs below the steps just waiting to tackle Gordon when he

stepped down.

They went to the village for weekends, where they played tennis and

danced in the Courthouse, where Mrs. Longden taught them the two-step and the

foxtrot. When Basil was born Mrs. Delaney made a tent with quince canes and a

nappie for the round basket in which the baby lay on a cushion, and a boy

carried it on his head and a girl followed with the portmanteaux. When Meikle

gave up his Melsetter farms in 1926 the Delaneys moved to their own farm Olive

Cliff.

~~~000~~~

|