Chapter 11

In 1920 ox transport was allowed as far as the Umvumvumvu but not inside

the district. Some of English�s farms were still infected with A.C.F., and he

and Longden undertook to fence the boundaries if they could pay for the

materials in terms of the Animal Diseases Ordinance: if the fence were erected

there would be no reason why ox transport should not be allowed throughout the

district apart from English�s land.

The Magistrate thought the offer was good and held out opportunities of

finally controlling and stamping out the disease in the area which had been

actively infected for some years and was the only one remaining, and the D.V.S.

agreed that it would be a very useful move. The C.V.S. refused to recommend that

the fencing should be done under the Ordinance, but English did get some

assistance for fencing.

Condy�s duties in inspecting farm schools included checking on whether the

teacher was doing his job and was suitable for the post, whether the farmer was

providing suitable accommodation, and whether all children were attending

school. After he and Madge Elliott were married in 1920 she accompanied him on

many visits of inspection, travelling by buckboard, going at the most 30 miles a

day with eight mules, and taking weeks to get round every school between Umtali

and Mount Silinda. When it was muddy and wet the flaps of the buckboard had to

be down and it was very dark and dreary inside. At the farms the people were all

the soul of kindness and hospitality, and the Condys were always invited at

least to a meal and often to stay the night, although they had their camping

equipment with them.

A teacher complained that no bath was provided and said that the farmer

could not understand why she needed one as there was a perfectly good stream

just outside the house. Condy insisted on a bathtub being provided and put in

her room each evening, with water heated in paraffin tins outside and carried in

for her. After she had been transferred the Condys visited the farm, and as they

drove up the long straight avenue to the house the setting sun was shining on

something hanging-up on the wall: when they got there they found it was the

bathtub, beautifully polished up with sand, hanging on the front verandah as an

ornament.

Checking on school attendance entailed travelling many miles to see all

the children, and Condy had to enquire into parents� circumstances and to

arrange for Government grants for all who could not pay for their children�s

schooling.

James Ward, R.A., came from England to visit his daughter Mary

Rose and his son Jim. At Umtali he was met by Fred Taylor and they went out in

Fred�s motor-side-car to meet the Mail Coach which brought Jim, Mrs. McLeod,

Allie and Harris and the luggage all packed tight. On their journey the Wards

were the only passengers, and the fare was �3.15 each for a single

journey.

The coach was as hard as iron and the bumping so awful that it might as

well have had no springs, and they had to hold on tight for two long days so as

to keep themselves on the seat. They paid 2/ 6d each for accommodation at the

two halfway huts in charge of a native attendant, which each contained two iron

bedsteads with mattresses of long straw and clean sheets and blankets, and

chair, table, waterjug and basin, towels and candles.

All through the journey the feet of the galloping mules raised a fine

red dust which covered the passengers and was difficult to wash and brush off.

Ward used his rug as a buffer between his back and the narrow backboard, but

owing to the excessive jolting it slipped off unnoticed and when they reached

Melsetter he authorised the Store-keeper to give 5/- to the driver if he

succeeded in retrieving it.

They spent a night at Melsetter Hotel, and in the morning Jim took his

father to tea with the Longdens, whom he described as the greatest and

wealthiest people in Melsetter and Mrs. Longden as a finely dressed lady of

great stature, and to lunch with Mr. and Mrs. Remmer a very nice lively woman.

George Rose had sent in two horses which Jim harnessed to the Remmer�s spring

cart and they drove out to Lemon Kop, where Mary and her children were waiting

to receive them, and where alterations were being made to the house. �Three new

rooms are already built of brick and will be roofed with ornamental tiles from

the Mount Silinda Works, and a huge kiln of new bricks is in the process of

burning.

�I have a very nice large bedroom with two windows: owing to the

verandah all round the house the rooms are dark, but most of the living and

meals take place on the verandah. The chief room is used as a dining and drawing

room: the walls are of cream-coloured plaster and the roof is lofty and

timbered; on the walls are many antlered heads of South African deer and

buffaloes, and my pictures, so that the room resembles something like a baronial

hall. In the evening we have a wood fire on an open hearth.

�The place is imposing with more than 600 head of cattle, 180 head of

sheep and numerous pigs, fowls and turkeys, six dogs and six horses. Everything

grows profusely and there are rows of fine orange trees, bananas, pineapples,

lemons, peaches, etc. and wheat and maize are also grown.

�There is plenty of shooting to be had: partridges, pheasant, wild

doves, and all varieties of deer, wild pigs and wild dogs. George went out on

Sunday and returned with two bushbuck: the meat is very close in fibre and

without fat, but eats tender when shaved in thin slices, and bacon or ham is

usually served with it.

�There is no lack of fresh butter, cream, milk, eggs, bacon and fruit.

Mary is famous for her butter and finds a ready market for all she can make, and

sends it off weekly in boxes. Of course, Snowball does most of the buttermaking,

Mary superintends and encourages her house servants to all diligence.�

In 1920 a Gymkhana Club was established, and two successful little race

meetings were held. The following year some good horses were entered, several

farmers had bought mares for breeding, and a valuable pedigree stallion, Jack

Tar, was imported and was available for service. During the decade the Club had

its ups and downs, but interest was maintained. Races were run from Cronwright�s

house on the Orange Grove Road, passing (or not) the Hotel, and finishing under

the gum trees near the Veterinary house.

In 1921 Chipinga residents, with a � for � Government grant, started work

on the Sabi road which was opened for traffic in April 1922 although it was some

years before it was in full use.

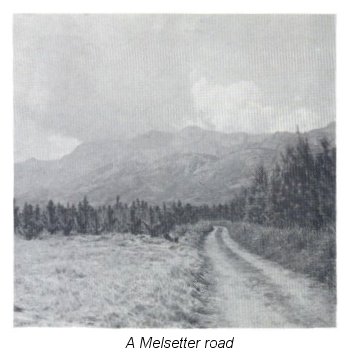

In order to find a better route for the Melsetter road out of Umtali to

avoid the heavy sand a surveyor was sent to investigate the possibility of

starting up the Vumba road, but he died on the job without submitting a report.

After much correspondence the Government decided to spend �500 on improving the

existing road. Nobody was satisfied with the position, and the Umtali Municipal

Council convened a conference which unanimously resolved that

a proper

survey, regardless of expense, should be made to decide the route for a

permanent metalled trunk road. Melsetter F.A. repeatedly pressed for

improvement, and sent a petition, signed by 80 people, although the number of

signatures was limited by difficulties of transport, of getting reliable

messengers, and of getting to meetings. Local contributions for the road

included 59 bags of mealies, one ox, and �169, with more promised if work were

started.

Two instances were given of how slow travel was because of the state

of the roads: a wagon on express business left Melsetter for Umtali on 26th

March and had not returned by 22nd April; and a family, including a lady 76

years of age who had never been in a train, took 13 days with donkeywagon from

Melsetter to Umtali. The apparently irrelevant remark about the old lady gives

rise to speculation: were they planning to take her on a train journey, and if

so, did they get there in time to catch it? Presumably the length of time in the

donkeywagon did not worry her unduly.

The 1921-22 rainy season was very mild, so little damage was done to

the road, and for the first six months of 1922 traffic was unimpeded, even

motorcars travelled without hindrance, but with almost no rain at all from May

to September the roads became very dusty and all vehicles found it hard work

ploughing through the sandy stretches. In July 1922 the first day return trip

was made by Overland of the Umtali Taxi Co.; it left Ijmtali at 4 am., arrived

in Melsetter at 11.30, left again at 1.20 p.m., and reached Umtali at

8.30.

In 1921 the Dutch Reformed Church built a schoolroom in the township to

which most farmers sent their children, but it fared no better financially than

the Government Hill School, and closed down for lack of funds in 1922. Its

establishment and the opening of farm schools had, however, affected attendance

at the Government School.

McLeod retired and James Harvie took over as Principal in 1921. That

year three temporary rondavels, destined to do duty for nearly 30 years, were

built in the space between the two dormitory blocks, one as the only sickroom,

one as a stockroom, and the third a staff sitting-room or matron�s

bedroom.

The Brent, Scott, Cronwuight, Ward and Edwards children from the

Chipinga district all travelled on donkeyback to get to school, and for some the

journey took three days. The Brents stayed overnight at Vermont, and they and

the Scotts left together at sparrowsqueak next morning. They spent the night in

very tatty disused pole-and-dagga huts under the gum trees on Albany, and rode

along the Nyahode valley next day, arriving in Melsetter about midday. On one

occasion Donald Scott was riding a donkey which had weaned her foal a day or two

before the trip, and hoped to have milk with the early morning coffee, but found

it was not a good idea. Later they had horses and did the trip in one day, 32

miles via Knutsford or 38 via Albany. Once there were four to get to school and

only two horses, so they had to ride-and-tie, and on this occasion were put up

by Tom Ferreira at Lavina�s Rust. One day Irene and Donald, on the last stint

from the Nyahode river, were chased by hungry kafir dogs and arrived in

Melsetter in a state of collapse.

Scholars were very much restricted to bounds in the early days, but

later, when there were only a few hoarders, they were allowed almost umlimited

freedom out of school hours. This gave them an opportunity to scavenge for food,

as what they got at the school table was very limited and of poor quality: the

complaint about the food was not just schoolboy bellyaching; Dr. Rose inspected

the fare and sent in an adverse report, and from official records it is learned

that the diet in 1921 contained a great deal of mealiemeal porridge. The

School�s deciduous orchard was the one place always out of bounds, but that did

not deter scholars from helping themselves when they could.

From Tanganda the Wards rode each term to Lemon Kop, spent the night

there, and reached Melsetter the next day. A farm labourer carried the trunk

containing their few necessary changes of clothing, and rode or led the horse

back to the farm. They used bridle paths extensively, and most journeys were

uneventful although occasionally there were flooded rivers to cross and once

Jimmy Ward was flanked by a pack of wild dogs for some miles which kept pace

with the horse as it galloped, trotted or walked.

Life at the School was pleasant. They had a tennis court, but their

main recreation was walking over the surrounding country with sometimes a very

chilly swim in the pool at the bottom of the Bridal Veil Falls. Teaching was

restricted to the three R�s, and some pupils had to do private study at home

before going on to Umtali High.

In 1922 the School had only five boarders, the boardinghouse was closed

in June, and Harvie left. Mr. and Mrs. Franklin occupied the school house and

looked after it. They boarded the only teacher, Miss Ford, and their elder

children attended the classes. To assist parents who had then to send their

children to Umtali as boarders, the Government made grants through the Land Bank

towards the cost of transport.

A.C.F. kept portions of the district in quarantine and, when some

restrictions were lifted, the prices had fallen to such an extent that farmers

preferred to retain their stock. 109 head of cattle died on Tilbury in 1921 and

there were successive fresh outbreaks.

|